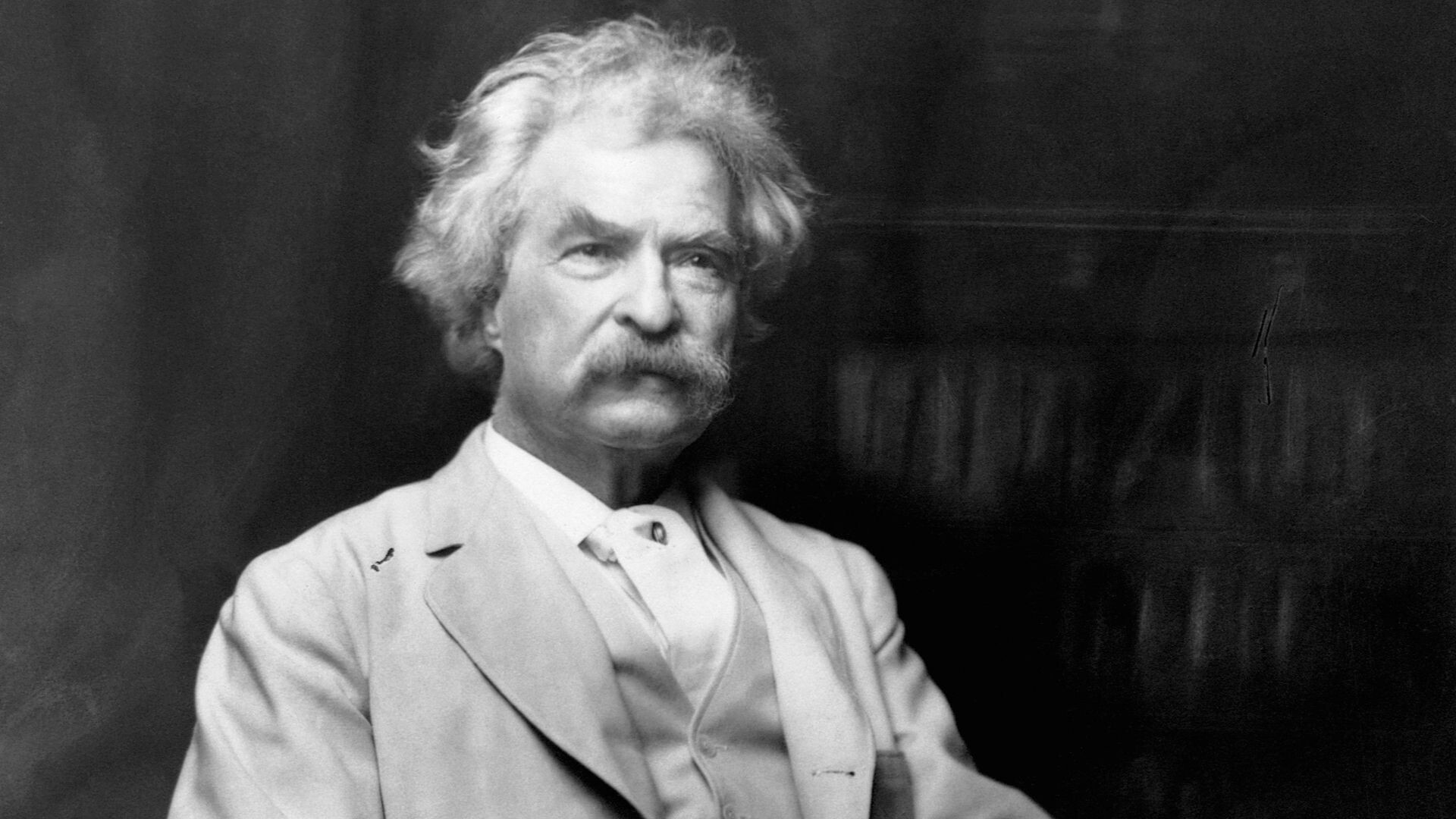

In a letter to the Sacramento Daily Union, Mark Twain once wrote:

“A photograph is a most important document, and there is nothing more damning to go down to posterity than a silly, foolish smile caught and fixed forever.”

So why the aversion to smiling—or even looking at the

camera—back in the day? The answer lies somewhere between slow shutter speeds,

strict social norms, and a widespread fear of looking… common.

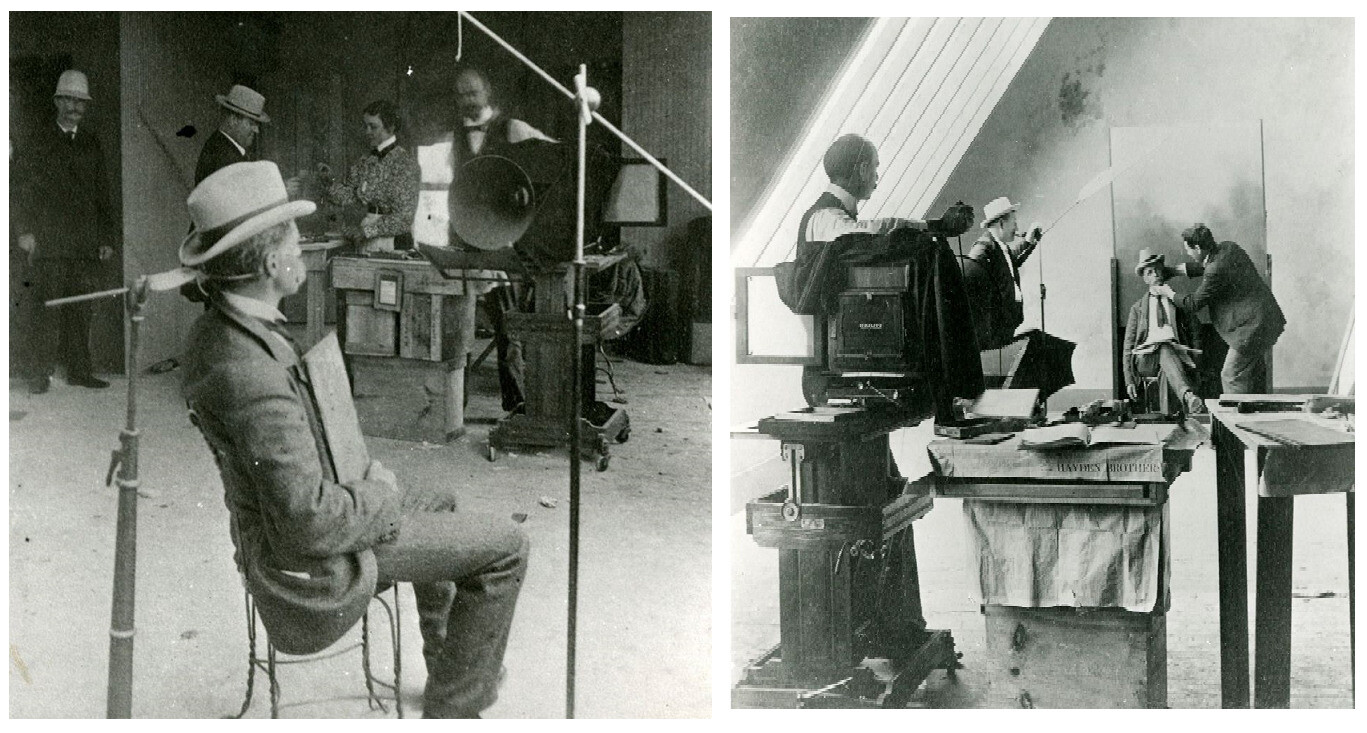

In the early days of photography, portrait poses were famously stiff. This wasn’t just a stylistic choice—it was a technical necessity. Early cameras required long exposures, often several seconds, and even the slightest movement could blur the image. To help people stay perfectly still, hidden braces were sometimes used to support their necks and heads.

Having your photo taken wasn’t the breezy experience it is today. It was often uncomfortable, and only the wealthier classes could afford it. For the nobility or well-to-do, sitting for a photograph was a rare and solemn event. The resulting image would serve as a legacy, meant to be taken seriously. A smile—or worse, eye contact with the lens—could come across as foolish or undignified by Victorian or Edwardian standards.

Photography, after all, borrowed heavily from the traditions of portrait painting, where solemn expressions conveyed virtue, intelligence, and status. The goal wasn’t to look friendly—it was to look important.

Diego Velázquez, The Triumph of Bacchus, 1628/29.

The first to smile in portraits? Not the upper classes—but actresses, dancers, and so-called women of ill repute, who used smiling photographs on their calling cards. Respectable ladies still preferred the look of quiet dignity.

But as Hollywood rose and the silver screen transformed actors into icons, smiling slowly became fashionable. Stars began to flash their teeth in publicity shots, and once they were seen as glamorous rather than scandalous, the smile was in.

Advances in oral hygiene didn’t hurt, either. As dentistry became more accessible and pearly whites more common, people had another reason to smile for the camera.

By the 1930s and ’40s, portrait photography had entered its dramatic phase: soft shadows, sculpted lighting, and what could only be described as romantic over-posing. Think Greta Garbo gazing wistfully into the distance. Still, direct eye contact with the lens remained taboo—too intense, too confrontational, perhaps. The mystery of the sidelong glance endured.

Fast forward to today, and you’ll find the exact opposite. We favour the candid, the natural, even the chaotic. What once seemed casual and unrefined is now the gold standard. Ironically, creating that “just caught in the moment” look often requires a skilled photographer’s touch—someone who knows how to frame, coax, and capture that elusive, genuine expression. This is the same approach used to capture business headshots or portraiture photography.

In modern portraits, we allow ourselves to be known by the viewer. There’s vulnerability, eye contact, and sometimes even laughter. In contrast, earlier portraits maintained a deliberate distance. The sitter didn’t invite you in—they kept you at arm’s length.

Somewhere between the collapse of Victorian restraint, the rise of Hollywood glamour and the availiblity of the photographic medium. Smiling stopped being a social liability and started being photogenic. And we’ve been grinning into the lens ever since.

Mark Twain might’ve rolled his eyes at our toothy selfies, but in the end, the “silly, foolish smile” turned out to be the most human thing we could preserve on film.